SUMMARY

Until now, technological limitations of agentic systems have hindered large-scale commercial deployment. That is now changing. AI agents are leading us toward Autonomous Organizations, a qualitative change in organizational design. The implications will be profound.

1. How did we get here?

Can firms have a will of their own? As we discussed in a recent article, this is an old idea, going all the way back to the 1950s [1]. The “will” is a result of decisions by many human actors, resulting in the appearance of a collective mind. An increasing number of these actors will now be AI agents.

AI agents are leading us toward Autonomous Organizations, a qualitative change in organizational design. While this is an area we have researched since 2016, it has long felt “early stage.” The technological limitations of agentic systems made large-scale commercial adoption unrealistic, even though they have been successfully deployed in specialized domains such as telecom, aerospace and the military. That is now changing.

Agents are first attested in the Early Bronze Age. In the Law Code of Hammurabi of Babylon (1755 BCE), no less than eight laws are dedicated to agents [2]. Roman Law, admirable for its elaboration of earlier concepts, specifies four different kinds of agents [3]. Roman legal concepts are with us even today, and our economy is full of different types of (human) agents.

Since the emergence of computing in business in the 1950s, we have recreated ancient management mechanisms in software, starting with accounting. AI agents in the enterprise can be viewed as a natural evolution in this respect. They are an important milestone in the development of AI as well as in management thinking.

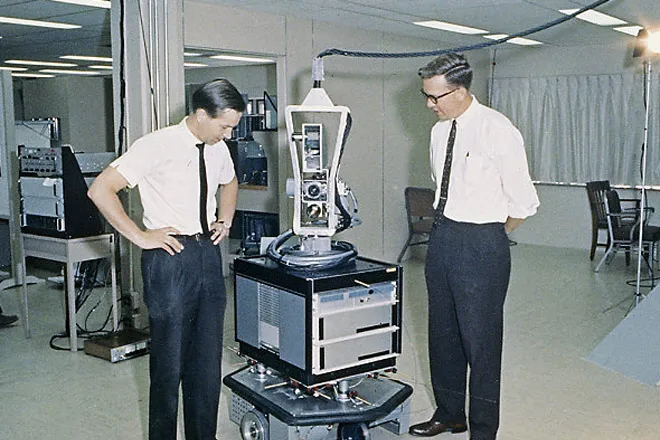

AI agents originated at SRI and MIT in the mid-1960s. In 1964, SRI applied to DARPA to fund a project to explore “Intelligent Automata” [4]. The project produced a now-famous robot named Shakey, which could perceive its environment through sensors, generate maneuvering plans, and replan as necessary. A key innovation was STRIPS, Shakey’s AI planner [5]. For

Sven Wahlström and Nils Nilsson with Shakey. Photo by SRI. historical perspective, it is important to appreciate that theorem-proving and problem-solving were always closely linked in the history of artificial intelligence.

Sven Wahlström and Nils Nilsson with Shakey. Photo by SRI.

In parallel, Carl Hewitt at MIT began developing what would become PLANNER-67, the first programming language explicitly designed for agentic systems [6]. Hewitt introduced the conceptual foundations that later evolved into the Actor Model—a formulation of concurrent computation that remains foundational to distributed systems and modern agent platforms.

What followed was fifty years of research on AI agents. Researchers addressed knowledge representation, querying knowledge bases, inter-agent communication, agent registries, collaboration, and competition. They built multi-agent systems, and by the early 2000s were incorporating statistical techniques for object recognition. Reinforcement Learning was also used to optimize behavior, but it was difficult to do because of the amount of training this required.

Another challenge was that agents did not know much about the world. Symbolic AI could provide reliable planning and reasoning, but agents had to be spoon-fed knowledge about their environment, and symbolic representation was the only option available. This limited the deployment of agentic systems to narrow domains, and commercial usage was almost non-existent.

The introduction of Large Language Models resulted in a reversal of circumstances. Access to knowledge about the world was now much easier, but it was immediately apparent that LLM-based reasoning and planning were nowhere near as reliable as what had been achieved with symbolic AI.

In the past two years, AI agent frameworks have moved beyond experimental prompt chains into more robust, production-grade platforms. Salesforce’s Agentforce exemplifies this shift by embedding autonomous agents within core business systems and data contexts, enabling agents to reason, act, and execute tasks across service, sales, and operational workflows without bespoke infrastructure.

The shift is visible in other frameworks as well. Frameworks such as AutoGen, LangGraph, and cloud-provider agent SDKs move beyond linear prompt chains by providing explicit state management, tool orchestration, and governance-enabling primitives. Together, these features address the brittleness of early LLM-based agent platforms.

There are still plenty of technical challenges that remain in today’s platforms. Because reasoning is not as reliable as we might like, monitoring of agents is still a necessity, with startups like Wayfound leading the way. Data management and quality are still an issue in many enterprises, with legacy systems that store data in separate silos. Trust and privacy concerns are widespread as well. Opaque Systems is a company worth watching here.

2. AI agents have gone mainstream

As we near the end of 2025, a number of reports have been released detailing challenges as well as progress. McKinsey reports that 23% of respondents are scaling an agentic AI system, and 39% said they have begun experimenting with agents [7]. This is an indication of strong interest.

Menlo Ventures finds a more modest 16% of enterprise AI deployments qualify as true agents; the rest are based on static workflows [8]. For startups the figure is 27%, which is quite a gap. Culture matters, as does the absence of complex legacy systems.

OpenAI reports quantifiable productivity gains for ChatGPT Enterprise users [9]. 73% of engineers report faster code delivery (still very much “the killer app”). 85% of marketing and product users report faster campaign execution. 87% of IT workers report faster IT issue resolution.

In a survey of more than 500 technical leaders across companies and industries, Anthropic reports that more than 57% of organizations now deploy agents for multi-stage workflows [10]. A further 16% have progressed to cross-functional applications spanning multiple teams. Looking ahead, more than eighty percent plan to handle more complex use cases in 2026.

The report also shows significant productivity improvements in software development, not just in code production but across other lifecycle stages as well. It includes perspectives from Accenture, Boston Consulting Group, and Deloitte. All three firms cite workforce transformation challenges, the need to handle non-human work products, and the difficulty of integrating a wide range of existing IT applications with agentic AI.

Given the still-modest state of production-level agent deployment in enterprises, it is easy to lose sight of how far we have come since ChatGPT’s initial release in late 2022. The gap between what is now technologically possible and what enterprises can successfully deploy remains large. Key obstacles include AI literacy limitations, integrating with legacy systems, and recruiting AI-savvy employees.

3. Interoperability and standards

As of early 2024, the vision of an “Internet of Agents” was shared among many early adopters. However, in terms of interoperability, AI agents looked like the IT industry before the Internet. It was obvious that a number of competing enterprise agent frameworks were emerging, and the lack of industry standards was becoming an urgent problem.

Multi-agent systems could also not easily cross organizational boundaries. It was clear that we needed a common registry for agents, so that they could be located and have their identities certified.

On November 25, 2024, Anthropic announced the Model Context Protocol (MCP), a standard for connecting AI agents to external tools, content repositories, and applications.

On March 6, 2025, Cisco announced a standardization initiative, AGNTCY, structured as a Cisco-led effort with industry working groups focused on interoperability mechanisms such as agent registries, communication, identity, and control planes. As participation rapidly expanded, Cisco announced on July 26 that they were placing reference implementations and specifications under neutral governance by donating the work to the Linux Foundation.

On April 9, 2025, Google announced the Agent2Agent (A2A) protocol, developed with sixty industry partners. A2A allows agents to announce and discover capabilities and exchange messages.

On May 14, 2025, Project NANDA was publicly launched at the MIT Decentralized AI: Internet of Agents Summit. NANDA is a research-led initiative based at MIT, with participation from academia and industry partners. It is intended to explore foundational architectures for large-scale, decentralized agent systems. NANDA has articulated a decentralized architecture for agent discovery, identity, and coordination, and has begun publishing reference designs and protocols aimed at enabling federated agent registries rather than centralized platforms. NANDA and AGNTCY are now collaborating on registry interoperability.

On June 23, 2025, the Linux Foundation announced it was taking over the A2A protocol, which was being donated by Google, together with SDKs and developer tooling.

On December 9, 2025, the Linux Foundation officially reorganized its AI agent standardization work as a new initiative called the AI Agent Foundation (AAIF). It also announced that AAIF was taking over Anthropic’s MCP project, goose from Block, and AGENTS.md from OpenAI. AGENTS.md is a file format for describing software project information that is handed off to an AI coding agent. Goose is an open source framework for developing AI agents.

In 2023 and 2024, there were early experiments by OpenAI, Google, Stripe, PayPal, Visa, and Mastercard exploring whether AI systems could engage directly in commercial transactions. By late 2025, these efforts have given way to coordinated initiatives from major platform and payments players: OpenAI and Stripe on agent-initiated checkout, Google on formalizing agent authorization and intent, and Visa and Mastercard on trusted-agent identity, tokenization, and network governance. Skyfire, a San Francisco startup, is developing a technology stack for agentic commerce. We will examine agentic commerce in more detail in a forthcoming article.

A tremendous amount of progress has been made in standards and interoperability in just over a year. In the year ahead, we can expect to see multi-platform, multi-agent systems in operation that cross organizational boundaries.

4. From Organizational Capabilities to Strategy

All organizations need certain key capabilities in order to sustain themselves. They must scan their environment for threats and opportunities, develop new products and services, source and manage suppliers, acquire and retain customers, deliver services and manufacture products, attract and manage human talent, and manage resources.

AI agents are being deployed to strengthen each of these capabilities, primarily motivated by effectiveness and efficiency (speed and cost savings). This is a natural development in the ongoing pursuit of organizational excellence. The more trustworthy agent platforms become, the more they will be used, and the more enterprises will benefit.

Most enterprises struggle with organizational change capacity. They have complex legacy systems, struggle to attract AI talent, suffer from poor AI literacy, and have conservative, risk-averse cultures that make innovation difficult. Gradually, however, we expect to see even slow adopters catching up. Those who cannot will not remain in business.

So what else can enterprises do to obtain or protect competitive advantage? AI agents are already in widespread use for both software development and hardware design, and they are sure to improve in capability. Every firm will use them to improve ideation, speed of development, quality, and performance.

Separate initiatives to improve innovation and execution can only do so much. To progress further, organizations must focus on the meta-capability that ties all the others together: strategy. A strategy is more than decision-making about resource allocation or which capabilities to acquire and improve. It is a hypothesis for how an organization can achieve objectives in an environment with uncertainty, adversarial actors, and limited time and resources.

In February 2025 we organized an event where we looked at the link between AI agents and strategy. Summarizing the history of strategy from the Bronze Age until the present time, we identified key cognitive tasks of strategy. It turns out that these tasks are very much the same tasks as AI agents already have to perform to reach goals they are given: obtain information about the environment, assess resources, develop a plan (hypothesis), implement the plan, and adjust along the way.

5. Speeding the evolution of firms

In 2013 Prof. Rita McGrath at Columbia Business School published the book “The End of Competitive Advantage: How to Keep Your Strategy Moving as Fast as Your Business” [11]. McGrath rejected the idea that an organization could find an advantageous market and develop a sustainable competitive advantage by erecting barriers to entry.

Common barriers include economies of scale, heavy capital requirements, access to distribution channels, proprietary technologies, raw materials, domain knowledge, favorable locations, and government regulatory capture. With exponential progress in technology and increasingly capable AI, such barriers are more easily eroded. Speeding organizational renewal therefore becomes mandatory for the survival of firms. Central to this will be the utilization of AI agents in the strategy function.

The work landscape now emerging involves humans and AI agents working together. Humans are used to configure and oversee agents (and agent monitoring tools), and humans also work with AI agents as tools. The more trustworthy AI agents become, the more we can take advantage of them as a coordination technology. We believe that routine management tasks, orchestrating work and monitoring its progress, will increasingly be performed by AI agents.

Orchestration of work also applies to strategy. We expect to see AI agents managing the flow of the strategy work itself, assigning tasks and convening sessions to review progress, and helping us make decisions. The obvious place for such innovation in the near term is in strategy management platforms, which currently manage processes, artifacts, projects, and goals. They are scaffolding for the human knowledge work involved in developing, executing, and monitoring strategies.

We surveyed strategy management platforms and found widespread usage of Generative AI, but not yet AI agents used for orchestrating and decision-making. There is no doubt that there is room for ambitious new startups to accelerate the development of this space.

The more we can trust AI agents and the more autonomy we can give them, the more we can accelerate strategy work and therefore speed the evolution of the firm. This makes it likely that firms will become increasingly autonomous.

Autonomous organizations are not necessarily devoid of humans. Rather, they shift human effort away from orchestration toward work that is directly value-adding. AI agents will increasingly take over orchestration, interfacing with other organizations (such as in supply chain management), develop strategies, and monitor their implementation. The “bureaucracy” of the organization will function like an omnipresent services layer to remove as much friction as possible.

The evolution of large organizations will speed up. Smaller organizations may have much less of a speed advantage than they did before, because the difference in coordination overhead will shrink dramatically. On the other hand, small organizations will now have access to the same sophisticated strategy capabilities previously reserved for large firms.

Narrowly focused service organizations may use no humans for operations, or may only use humans to perform service work where human judgment is needed. Locating and negotiating terms with the latter will be facilitated by marketplaces that are already in existence.

6. Our autonomous future

Pre-industrial management went from simple toolmaking, to agriculture, to large, hierarchical organizations — empires. The Industrial era contributed standardization of workflows and components and the use of mathematics to make decisions about optimizing both. We also began to understand more about psychology of work. As we progressed from hunter-gatherers to agriculturalists to city-dwellers to enjoying the fruits of mass production, centralization increased.

Post-Industrial management thinking seeks to address a very different set of circumstances — the combination of exponential progress in technology and decentralized value creation. AI agents will further enhance the amount of value that can be created with very small firms, even by a one-person firm.

Full autonomy is not here yet, and its emergence will be a gradual process. While significant technical and social obstacles remain, we believe the progress toward increasing autonomy is inescapable. Autonomous organizations will evolve faster and execute better, and they will deploy human talent where it adds the most value.

The first fully autonomous organizations will have a narrow focus and they may also have very short lifespans. We have previously written about higher-order organizations — organizations that have as their purpose to spawn new micro-organizations [12]. We will probably see these come into existence first. Larger, more complex organizations will be slower to evolve toward autonomy.

While agentic commerce is still in an embryonic stage and focused on consumer purchases, the deeper implication is that AI agents will accelerate the optimization of entire supply chains. Agents will not only orchestrate resources inside the firm, they will develop just-in-time business models and orchestrate entire ecosystems.

Leadership, culture, and human development will become more important than ever, but

with the nature of organizations changing rapidly, we will need to think about these

subjects as increasingly decoupled from formal organizations. Organizations are a means to an end: to orchestrate resources for collaborative exploration, innovation, and value creation.

References

1. F. L. Odegard, “Can a Firm Have a Will of Its Own?,” *Post-Industrial Institute*, Dec. 4, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://post-industrial.institute/can-a-firm-have-a-will-of-its-own\

2. C. H. W. Johns, The Code of the Laws of Hammurabi. Edinburgh, U.K.: T&T Clark, 1904.

3. R. Zimmermann, The Law of Obligations: Roman Foundations of the Civilian Tradition. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford Univ. Press, 1996.

4. N. J. Nilsson, Shakey the Robot, SRI International, Artificial Intelligence Center, Tech. Note 323, Menlo Park, CA, Apr. 1984.

5. R. E. Fikes and N. J. Nilsson, “STRIPS: A New Approach to the Application of Theorem Proving to Problem Solving,” Artificial Intelligence, vol. 2, no. 3–4, pp. 189–208, 1971.

6. C. Hewitt, “PLANNER: A Language for Manipulating Models and Proving Theorems in a Robot,” in Proc. Int. Joint Conf. Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), Washington, DC, USA, 1969, pp. 295–302.

7. McKinsey & Company, The State of AI — Industry Perspective. 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai

8. Menlo Ventures, The State of AI Agents: Market Landscape, Use Cases, and Investment Trends. Menlo Park, CA, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.menlovc.com/perspective/the-state-of-ai-agents

9. OpenAI, The State of Enterprise AI — 2025 Report. San Francisco, CA, Dec. 8, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://openai.com/index/the-state-of-enterprise-ai-2025-report

10. Anthropic and Material, The 2026 State of AI Agents Report. Anthropic & Material, 2025. [Online] Available: https://claude.com/blog/how-enterprises-are-building-ai-agents-in-2026

11. R. G. McGrath, The End of Competitive Advantage: How to Keep Your Strategy Moving as Fast as Your Business. Boston, MA, USA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2013.

12. F. L. Odegard, Digital Myopia and the Coming of Post-Industrial Civilization. Post-Industrial Institute White Paper, 2019.